|

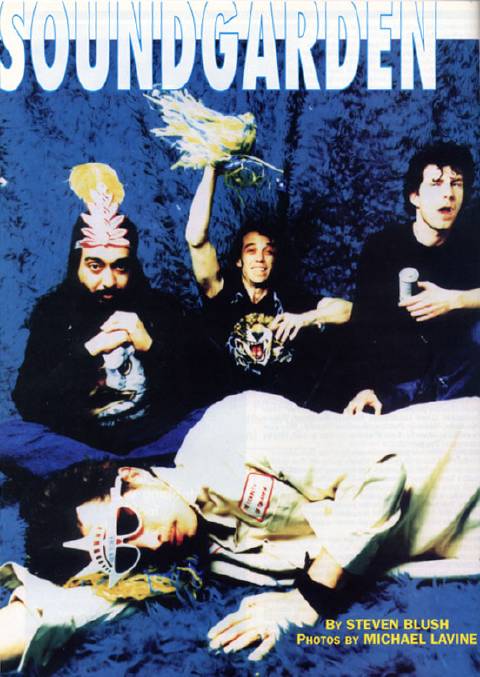

SECONDS SOUNDGARDEN

"You can take any subject and ask us about it and I feel confident our band will present a more intelligent response than any other band." What else can be said about SOUNDGARDEN that you haven't heard a zillion times? They're the Seattle band that started all that Grunge shit in the first place; the ones that propelled Hard Rock out of its power-ballad poodlehead doldrums and (semi-) straight into the Millennium. Frontman CHRIS CORNELL is the musical icon/sex symbol that defines post-Alternative Pop Culture — supercool to male fans and dreamy to the women, especially back in the day when he was the longhaired, brooding, bare-chested boy toy with the Doc Martens and the droopy shorts. KIM THAYIL's rippin', bleary-eyed axe tones have been appropriated (read: ripped off) by every lame-ass multi-Platinum flannel-flyin' band in America. Bassist BEN SHEPHERD and drummer MATT CAMERON might be the greatest rhythmic tag team since John Bonham and John Paul Jones.

And speaking of Led Zep, Kim 'n Chris 'n crew are so fulla Page/Plant-isms that they are the new Led Zeppelin — the new Classic Rock heroes of our anti-hero age — straight down to the from-the-groin wails and bombastic riffage. (Hell, is Down On The Upside the new In Through The Out Door or what?) And like Zep, these guys can he horrifically dull in concert. In a word, this is Rock with a capital "R." I could sit here for hours and tell ya about the good ol' days before Nevermind, when I heard the first Soundgarden 7" with Faith No More drummer Mike Bordin — who was trying to get ex-drummer Cornell to replace troubled original FNM vocalist Chuck Moseley — or about the quartet's first national tour in support of Ultramega OK with original bassist Hiro Yamamoto, or about the disjointed Louder Than Love tour with Rock Dude-turned-military man Jason Everman, or the now seemingly implausible dates in support of Skid Row and Guns 'N Roses, or the genesis of the multi-Platinum Temple Of The Dog project in tribute to Chris' overrated dead junkie roommate Andrew Wood of Mother Love Bone "fame" — but that would waste too much ink and paper and time and energy. Let's talk about the here and now: Soundgarden are the premier Rock ensemble on the planet, and the only thing that can stop them is themselves. But luckily, all the limos and hangers-on and bullshit adulations haven't affected their artistic vision (too much). While chillin' with these guys over numerous beers at Manhattan's celeb-friendly Righa Royal Hotel, it becomes increasingly clear that Soundgarden have finally come of age: mature men comfortable with their power and influence, articulate and knowledgeable of Music History and their position within it. The song remains the same?

CAMERON: That's a good compliment. SECONDS: Like Zeppelin, you guys can be a very noisy live band. CAMERON: A very shitty live band is what you're saying. Yeah, we're definitely not on all the time live, but that's what makes it exciting. If one of us fucks up, it instantly turns into Jazz. We just try and land on our feet somehow. SECONDS: Was it a statement to produce the record yourselves? SHEPHERD: We knew how to do it ourselves. CORNELL: From my point of view, it's whatever it takes to make the best record. Every time we've had a producer, that was the idea — "Wow, this guy might be able to make us sound like we want to sound." We realized these people aren't geniuses that can come in and do that job better than we can. We're happy with all the records we've made but every record left something to be desired. There was a certain amount of disappointment. We realized we gained something from having a producer but lost something we specifically wanted. Having done quick recordings of demos and B-sides on our own, there's an element we recognized we were missing on our records. You start thinking, "Maybe it's because there is a producer." We're either lagging on the responsibility because there's someone else we can lay that responsibility on or because there's four very opinionated people in the band, and a fifth guy is too many cooks and convolutes everything. It has to go down too many mental roads, which dilutes it. THAYIL: We're certainly not easy people. A producer might be able to click with a couple of guys but all pistons have to be firing at a Soundgarden recording session in order to make it satisfactory. Everyone's a strong personality and no one's going to take shit from anyone. If the President was here and told us, "I think you should do this ..." I'd say, "I'll do that if I feel like it." Everyone in the band has that attitude; it's not an ego thing but hard-headedness. I don't think we've ever been in a situation where all four guys were satisfied with the relationship with the producer. Matt was the one who said, "What do we need another guy for? We can do this. We know what we want, we know what we want to sound like. We can make this record." What Matt specifically expressed was confidence in our ability to do it. SECONDS: There's always been a slight bitterness about other bands ripping you off. THAYIL: I'd be at more fault than anyone else in the band. It's a hard thing to swallow, to put in a lot of effort to see someone else copying what you're doing with minimal effort and taking the rewards. Here we are with a clear idea of what we were doing and someone else decides it's a hip thing to do and they're living the life of a Rock Star. I don't want to slam a band but it was ironic and disappointing to me. SECONDS: Is there a violent aspect to your music? SHEPHERD: Sometimes. Actually, most of my songs are written on acoustic guitar. They're mellow denim-and-leather shit. Now I'm back in the mood of writing hard power chord progressions. Usually when I'm playing music, I'm less violent. When I don't play, I start getting crazy. SECONDS: What happens? SHEPHERD: I mouth off like a dumb-ass. SECONDS: How do you work it out? SHEPHERD: I don't. "I want people's heads to spin. I like music

that makes my head spin; SECONDS: How do you compare yourself to the other bass players in the hand? SHEPHERD: Hiro Yamamoto was the king. There's only a few I've seen that I think are good and he's one. SECONDS: Matt, give a short critique on all the bass plovers. CAMERON: Before I joined the group, I was really into Hiro. He was in a couple of other bands in Seattle and I thought he was just awesome. I always wanted to play with him so when I joined up with him, it was instantly my favorite thing about the band. He had a really fluid style and definitely defined the early sound of the band. Once Chris started writing more tunes, Hiro's role took a back seat because he wasn't writing as much. He got disenchanted with what we were doing and eventually faded out. Jason Everman was the next guy and he was a complete 180. He had a strict Rock root note style of bass playing. It wasn't as challenging and, of course, his personality and whatnot didn't work with the band. Then we got Ben and he brought so much into the band with his songwriting and musicianship. He had never played bass before, so it was a completely new thing for me. It was really exciting for me because he approached it in the most peculiar ways that made him fun to play with. We've played in other musical situations like Hater where he's playing guitar and he just has so much to offer. He dominates any musical situation he's in because he's such a creative dynamo. "I recognize I'm not going to be happy and it's not going to change if I whine about it." SECONDS: What's the status of Hater these days? CAMERON: We've got a new record kind of waiting around. Ben wants to remix stuff but it's pretty rockin' and ready to go. We've been in some legal battles with The Haters, so we might change the name. They're this weird experimental group from San Francisco that's been around for awhile. We didn't know about them and named our band Hater and then got this hate mail from The Haters. SECONDS: You still reflect on Hiro a lot. Are you finally over him? THAYIL: Hiro isn't an issue. I was talking to Michael Lavine and I saw pictures with Jason. Jason worked hard and contributed to the band. SECONDS: Jason Everman was thrown out of Nirvana and Soundgarden. THAYIL: "Thrown out" is a weird way to say it. He never really fit. It's like three wheels on a truck and the spare tire was underinflated. CORNELL: I don't know how he became a part of Nirvana. We lost a founding member that was a quarter of what we were, so we were really protective of the three quarters left. We were pretty vocal about that with Jason, and we weren't making any promises. We felt he could participate because he knew all our songs from Day One. We'd name a song, count it off and he'd play it. THAYIL: He was a perfectly competent musician and he had a perfectly competent work ethic. He'd be a steel part for any band. His talents were there and there was no misjudgment on our part or Nirvana's part in regard to his talent. There's a chemistry thing — we're particular people. Every band is a component of its parts. We're a little more difficult to satisfy than other bands. CORNELL: I don't want to say we were spoiled but Kim and Hiro and I knew each other. If we didn't like each other, we wouldn't have started the band. We were already friends and became friends more and more as time went on. We knew Matt as a friend, so it wasn't a drastic move to bring him in the band. Scott Sundquist, the drummer we had before Matt, was a friend of mine. THAYIL: He's still one of me and Chris' best friends. Every week Chris and I will hang out with him. CORNELL: With Jason, he was from Seattle, so it wasn't like this mail-order bass player. THAYIL: He's hip, too. He knows what's right and wrong about the music. CORNELL: We knew of him but he wasn't our pal, somebody we knew we could get along with in any situation that might come up. There wasn't that glue factor. With Ben, when the chips are down we all defend each other no matter what. There's nothing that could happen to any of us where the other three guys aren't going to be there. We were friends with Ben and he was someone we jammed with at the same time we jammed with Jason. When Jason didn't work out, it wasn't because he wasn't good at what he did. We didn't need to go find someone better than him; we needed to find a kindred spirit that we'd hang out with anyway. We realized that was an important thing. I remember when we were in Europe and it was obvious we weren't gelling with Jason after playing sixty, seventy shows with him. We were having a discussion and I remember saying, "I don't want to go through an audition period. If we're not going to have Jason in the band, let's just go home and ask Ben to be in the band." I figured it out, probably later than Kim did. CORNELL: When you look back at that period, we didn't have the tools to reach different audiences. We were on an indie label and sold as much as a Rock Band could sell on an indie label. We'd done all the tours; we were on top of it. We signed with a major and figured, "It's a step up." THAYIL: We were ahead of everyone at the time in that particular market. We would have offers to tour with Metallica and AC/DC. Opening up for someone was the closest we could have gotten to a large audience. CORNELL: It was like, "We can do what we've been doing or we can do something different." In retrospect, we were like aliens on another planet. The Guns 'N Roses tour — I don't look back at that and think of it as an amazing period; I look back and think how weird it was show after show. I respect them for what they want to do — THAYIL: They were totally supportive of us. CORNELL: Totally. But as far as the situation we were in, I don't know that it necessarily helped us other than that we got to see this whole other side of things. We got to make the decision which way to go. CORNELL: In some ways, it may have hurt us. There were people whose judgment I respected who said, "You guys are on this fence. You're not Metal, you're not Punk, but people can perceive you either way. Touring with these bands makes it easier for people to perceive you in a way that might be unappealing." What I saw as the benefit of the tour was that we were hitting markets we couldn't have sustained headlining our own tour. No promoter would take a chance on us unless we played a small club. Even then, those markets were not Soundgarden-friendly. Playing with Skid Row and Guns 'N Roses, our fans would have an opportunity to see us. They came out and bought the merchandise. There were days on tour with Skid Row where we out-sold them in merchandise. That was a surprising thing. We knew we had an audience. If we had to do it all over again, I still can't see any other decision that would have been better. We realized we had a lot more fans in Middle America than we thought and we established new ones. SECONDS: Now, you've turned into the band you would have rebelled against when you were fifteen! SECONDS: You've learned from the Grand Funks and Foghats? SHEPHERD: That generation was completely different and I don't understand it. This is going to sound square coming out of my mouth, but right when Husker Dü got signed, it seemed the generation of indulgent, bloated Rock Stars was over and the new kind of Rock Stars coming out were normal Joe Blow kids that knew better than to do Coke every ten minutes. But now, once again, the Heroin thing — it never goes away. It's all media crap to think it actually comes and goes — it's been there the whole time. SECONDS: Isn't mind-altering part of the Rock process? SHEPHERD: That's what you're playing music for. You're supposed to alter your mind — but with music, though, not the other shit. THAYIL: Since we first started, we talked about why our favorite bands broke up. We said, "The biggest obstacle between a band and its success is longevity. If you like what you're doing, how do you keep liking it? What has killed bands we like?" We all had our favorite bands that ended prematurely. MC5, The Stooges — they all ended prematurely. Kiss ended prematurely, believe or not. SECONDS: It's easy to say afterwards, "Here's what this band did wrong," but when you're living it, it's a different thing. THAYIL: But those bands didn't have much reference. We have reference points for all those experiences — big egos, guys leaving for solo careers, bands breaking up because they don't like one guy, someone marrying the backup singer when someone else in the band has a crush on her — Anita Pallenberg kind of crap. SECONDS: You guys don't have the sex-and-drugs baggage. THAYIL: No, but like any business, there's things to attend to. It's not just about rockin' out. The fact that we're level-headed allows us to keep a perspective. These are things that have happened to bands but we've tried to make sure every individual in the band is happy and everyone's interest is being represented so we can do the job of writing songs and rockin' out. "I'd be surprised if you name a band in recent Rock history that's doing what hasn't been done a million times before." SECONDS: How do you deal with bandmembers when they get too big for their britches? CAMERON: We let each guy do his own thing if they feel they need to spread their wings. We don't really run across it too much. Kim gets freaked out sometimes by the adulation that comes with being in a famous Rock Band but maybe down the line he'll have an acting career. SECONDS: People expect Rock Musicians to have something profound to say. Do you? CORNELL: There's not many topics you could bring up that we don't have something to say about. Some people may pick a specific thing and decide to speak of it a lot but I'd be surprised if you name a band in recent Rock history that's doing what hasn't been done a million times before. Whatever our opinions are, we might agree with bands that have very specific things to say, like Rage Against The Machine, but I don't think our ability to create music has anything to do with educating people about our ideas. THAYIL: We'd like people to reach conclusions based on their ability to think for themselves. We don't want them to have political opinions based on the fact that they share sentiments with us. It's irresponsible for entertainers to take advantage of their influence to encourage a particular belief. What is responsible is to give people the tools to think independently and reach conclusions. You can take any subject and ask us about it and I feel confident our band will present a more intelligent response than any other band. It's not based on sentiment. We can generate ideas and support them based on notions of fairness and mind-ones-own-business. It's part laissez-faire capitalism and part of it might have some collectivist sentiment. Ultimately, the ideas are supportive of the individual. They're not some weird abstraction that people have to adhere to and buy all the propaganda that goes with it. There are complicated issues where you have to weigh utilitarian happiness. "How much happiness is gained by this decision? How much happiness is gained by that decision?" Even those things can be solved. CORNELL: No, but that has nothing to do with things. Who can say they're happy and shut the book? "I'm happy — end of discussion." I can't say that. It seems like you'd have to be on strong prescription medication to say that. I can say I'm happy now and something two hours from now might make me not feel that way. It's a transient reality no matter what. You can look back at different periods of your life and think, "Yeah, I was happier then," but that's hindsight. You can't say, "I'm going to be happy next year." THAYIL: You can be content and satisfied, but you're not happy if you're complacent. You're certainly not going to be happy in a situation where you realize your limitations. With me, I resigned myself at a very young age to the fact that I'm never going to be happy. There's no reasonable way to acquire that. There's a lot of superficial ways to acquire happiness. Being amused isn't being happy. I recognize I'm not going to be happy and it's not going to change if I whine about it. What you realize is that you're incomplete and finite. You grow and challenge yourself, like Sisyphus. You're pushing the boulder up to the top of the hill — and for what? If you reach the top, the ball rolls down again. If I was omnipotent or omniscient, happiness wouldn't even be an issue. It would be a whole other intellectual state that wouldn't require something as petty as emotions. Because I am bound by emotions — like all of us are — just suck up your teeth and make a fist. SECONDS: What kind of reaction do you want? THAYIL: I want people's heads to spin. I like music that makes my head spin; that's what we all like about our band. "Oh wow, we played that!" It's not just me going, "Hey, I did that," it's, "Wow, listen to what Chris is singing! Listen to what Matt's doing!" CORNELL: There's a certain amount of escapism that's not credited as being important in music, even though a lot of Pop Music has a huge cultural impact. Is it something that's identifiable where someone can say, "This is part of me"? No matter what, it ends up being entertainment and escapism. When you say "entertainment and escapism" it trivializes it — but maybe it should. I don't think music should be more than that. THAYIL: Escapism is one of the evils according to the New Wave manifesto. First of all, entertainment has an escapist quality to begin with. Just because it's not fantasy-oriented doesn't mean it's not escapist, but somehow people believed that in the early Eighties with Punk Rock. Punk Rock had this gritty street thing but it doesn't change the fact that it's entertainment. You receive a certain amount of escape dollars just from watching a political campaign. It's like the World Series. What people find in entertainment is ultimately escapist, but at some point in the Seventies it was this Prog-Rock fantasy that was a non-real thing. You don't have to deal with capricious whimsies in order to be escapist. Escapism doesn't mean you're not dealing with the issue; escapism just allows you to explore yourself as an individual and other potentials for your life. Entertainment serves that purpose. We wouldn't deny that what we do is escapist, because it is — and just as much as Lou Reed or Bruce Springsteen. SHEPHERD: Punk just got accepted somehow. This generation is more angry and fed up with the Fifties version of life, the Sixties version of life, weird Seventies version, lame Eighties version. There's nowhere to go, but the media reforms and regurgitates everything and people are stupid enough to buy it all over again. But there isn't anything new sticking out. "It's irresponsible for entertainers to take advantage of their influence to encourage a particular belief." SECONDS: What did you retain from those Punk influences? CORNELL: Part of the DIY ethic. Just where we align ourselves. I always thought of Punk as being something that was anti-sexist, anti-racism, and anti-indulgence. SECONDS: I'll leave it at that. CORNELL: But you didn't ask us anything about the songs. SECONDS: I feel like it's a record that speaks for itself. CORNELL: I think in a way, you're right — it does speak for itself. How many times does somebody want to read a band's take on their new record? The record's out there. At the point that it's released, it stops having anything to do with us. The less it has to do with us, the better. SECONDS: Is Soundgarden family entertainment now? SHEPHERD: Even though we won two Grammys, I still feel like a dark horse, the evil uncle in the closet. The bottom line is: we're four guys who are confident in what we do. SECONDS: What do you expect from the listener? SHEPHERD: I don't. I think they'll listen but I don't know what they'll get from it. |

|||

| BACK ISSUES |  |

.45 DM |

| ARTICLES | AUTHORS | |

| HISTORICAL | LINKS | |

| Contact: info-at-secondsmagazine-dot-com | ||

SECONDS:

SECONDS: THAYIL:

THAYIL:

SECONDS:

SECONDS: